Monique David-Ménard

(De Paul University, October 2011)

It is not often that studies on Foucault’s work take an exclusive look at The Archeology of Knowledge. Instead, the text is presented as a text that is summing up work that has been achieved throughout the first great studies: The History of Madness, The Birth of the Clinic and The Order of Things. Or again, Foucault the historian of science is separated from Foucault, the thinker of norms, dispositifs and knowledge/power. One knows in particular that, when it comes to the division of his body of work, the reception of Foucault has been different in the United States and in France for a long time. But what ever those different starting points to the work might have been, The Archeology of Knowledge is never singled out. So I would like to show that this book is an experience of thought of an unparalleled conceptual audacity, with which a new kind of analysis of discourse is brought into focus by Foucault, which straightaway generates what he would be naming later, in Discipline and Punish, a “dispositif”. So what is first of all most remarkable is that in the analysis of language he has left the idea of literature as a metaphysical experience behind. It is in The Archeology of Knowledge that he develops the instruments in order to elucidate discursive operations as operations.

For several years now, in approaching concepts such as dispositifs and discourses, Foucault has been somewhat made into a thinker of the perfomative, a thinker of language games. In other words, a proximity with Austin and/or Wittgenstein is being established. I wish to show that the analysis of the statements in 1970 converges neither with that of Austin nor with that of Wittgenstein. Since Foucault, under the names of the statement, of discourse and of discursive practice didn’t describe an act internal to discourse, but relations that “are, in a sense, at the limit of discourse” (A.K. 49). How could this limit of what is said be described, without conceiving it as a limit of the sayable which would fall into the field of the

metaphysical experience of the unsayable? That is the path followed since Raymond Roussel thanks to The Archeology of Knowledge. The concern is to delineate statements as operations, as acts so to speak, but impersonal ones and in which a relatively stable temporality doesn’t adhere to the execution, repeated each time in speech acts, of the act of speaking, even if it is implicit.

What is a statement?

With the identification of what he calls a statement and a group of statements forming a discursive practice, Foucault pinpoints a materiality of language that actually subverts the duality of words and things.

A statement is a sequence in language which defines itself through something other than its meaning (and the endless annotations that it calls forth), other than its logical organization (which implies the question of its reference) and other than its signifying structure (which privileges the empty space which actively binds the signifying structure to a system of signifieds). A statement is characterized by its “external relations”, meaning the rules by which it finds itself aligned, in a stable fashion, for a certain time, with other statements, with institutions, with usages, with procedures and instructions. The phrase “species evolve”, for example, does not mean the same thing in Lamarck and in Darwin, since only for the latter it has the function of a principle that accounts for a radically new aspect of the law of life, in connection with natural selection. As is known, natural selection is a method that Darwin transforms into a law. But the Darwinian statement, simply because of its character as a principle overturns theology, the morality of creation, as one can see today with the political and religious movements in the United States that try to ban it from being taught in schools. A statement is never just a vessel for knowledge, it defines a “function of existence” that weaves itself according to stable rules between institutions, usages, forms of knowledge and practices. It doesn’t have a reference, like a “pure” discourse – which is opposed too one-sidedly to “things” – it has a “domain of coexistence” formed through exterior dimensions, while the former and the latter are connected by it. Another example: a phrase that is uttered in everyday life and replaced by a writer in a manuscript though the course of writing doesn’t appear doesn’t belong to the same statement: whether the phrase is pronounced by a person or attributed to the anonymous voice in a narrative said to be the author’s, the phrase would belong to an order that is different to the “materiality of the institution” (A.K. p.115). Out of the same reason a work is not the same statement before and after its author’s death: the juridical order of the oeuvre demands a different kind of relation to the social and cultural body. Last example: “dreams have a meaning” is not the same statement when uttered by Artemidorus of Sicily in the second century A.D. or when uttered by Freud. With the latter, the statement is connected to the clinical technique of the cure, to the hypothesis of the sexual unconscious, to attacking the distinction between the pathological and the normal which, a little like the Darwinian theory of evolution, made it so closely contested because it was defined by the limitation of the field which closed off its immanent rules. Statements are rare, Foucault writes as well, as opposed to the unlimited linguistic elements that can make up a language, grammar or logic. The rarity of a statement in 1970 thus points already to the inseparability of knowledge and power which Foucault will later address explicitly, and this political aspect which makes the statement a disputed matter is closely connected to another practical attribute: there is something technical or operational in that which delineates a statement as in that which forms a dispositif. And operability is closely connected with rarity, that is to say, with the limitation of statements which are thus already, in 1970, defined as dispositifs.

The operational and the technical in discourses

To my knowledge, language has never been tackled in the way Foucault has done since The Archeology of Knowledge: not as describing the seizing of things with words, not as describing a fold or a knot between being and language, but as understanding the statement in its technical function. Not only in the sense of technique of writing or of rhetoric – that he had done emphatically in his Raymond Roussel – but in the sense that the statement is the production of an impersonal act which implements relations that intersect with the signfiying function without deriving from it. As we have seen at the beginning of the chapter at hand, he doesn’t reject the analysis of language in terms of signifiers and signifieds in an absolute fashion; he fights for the right to show a different aspect of the formation of language, which, incidentally, overlaps with the organization of signifiers or the rules of grammar and of meaning, without however reducing it to that.

It is very interesting to refer to examples of statements that are situated between the technical and the mathematical without quite belonging to either field: the succession of letters on the keys of a typewriter which is listed in a typing manual is a statement: AZERT in French, even though neither the letters in their materiality, nor the material of the writing mechanism are a statement. That is to say this succession of letters forms a sequence which makes typing in a given language easier. At issue is neither knowledge, nor the single technical object that is the typewriter, nor a logical order, nor a grammatical sequence, but rather the relationship that is established between the structure of a language, a technical object of writing and the strategy that consists of choosing the arrangement of the letters that are used most. An operation confers onto the machine its function for certain uses of writing and communication. This combination of given facts entering a field of exteriority is what defines a statement. That a statement can’t be an item of knowledge is specified through the second example, which concerns an item of knowledge. But for Foucault the statement, within that knowledge, belongs to the same register of operability as “AZERT”: the list of numbers picked at random, which statisticians sometimes use, is a sequence of numeric symbols. They constitute a statement because they are a mass of numbers obtained by “procedures that eliminate everything that might increase the probability of the succeeding issues.” (A.K. 96) In that succession of numbers a pure coincidence doesn’t exist, since not privileging any variation in the way the numbers occur falls under a “procedure”. The statement does not coincide with a theory of probability such as mathematics, but rather consists of an operation that assures equivalence when it comes to the choice of numbers. In picking these examples, Foucault insists above all on the fact that a statement is not necessarily a sentence. But he shows as well that it is not the element of knowledge in itself that makes up the statement; the conditions of the discourse do – be it material, institutional, operational. The statement can be discovered in the same way in the operational element of a mathematical theory connected to the practice of statistics, as in the simplifying procedure, which doesn’t belong to a theoretical knowledge, that is the sequence of letters institutionalized in the typewriter and for a given language. The rarity of a statement produces itself through this type of choice. And it is as such as choice that the statement is a “function of existence” (A.K. 97). It realizes a relation that constitutes its order which is connected to a technique, a practice or an institutionalized language in one case, and mathematical theory in another. These are not virtual factors that govern the scarcity of statements (Deleuze). These are not the sole components of a structure that defines language (Lacan).

The expression “function of existence” is truly remarkable, and shows nicely what is left of Kant in Foucault: the Kantian transcendental is not merely a philosophy of the a priori (that is to say the idea that if reality consists of rules, then these rules originate from our mind independent of what presents itself, each time different in the experience as opposed to what one can anticipate). When it comes to this autonomous origin of the a priori, thought of as the anteriority of the requirement of categories that “come before that which presents itself to our intuition”, Foucault isn’t Kantian. That’s what makes him talk about a historical a priori. Where Foucault certainly is Kantian, is then where, for Kant, finding a solution for a given problem means finding a real object for an idea that, taken in itself, does not have a relation to reality. Kant speaks of the “false subtlety” of formal logic. In turn, Foucault says: a statement opens up the possibility of objects. With that his method keeps the appraisal of what Kant called the “transcendental”. The statement determines itself as a function of existence that cannot be reduced to either the materiality of the symbols of writing or to that of pieces of a machine, or to an ideal object formed by categories or by calculation, but that is defined as a functioning, connected to a “system of reference” which organizes the circulation between material and use, between institutions and other statements. The statement exhibits a “domain of coexistence” and not a reference, a term that applies to formal logic. The statement designates the register of reality with its archeological method defining relevance: “The statement cannot be identified with a fragment of matter; but its identity varies with a complex set of material institutions.” (A.K. 115)

Emphasizing this operative materiality of statements is all the more remarkable and difficult to discern as it concerns language phenomena that one usually approaches in a different way. What is established in the kingdom of signs without this institution be reduced to a convention? “AZERT” or the compositions of Magritte, or the procedure of obtaining a sequence of numbers in statistics are examples offered to us in the same way as the dispositif of the prison, that of sexuality or that of governmentality.

“This is not a pipe”

Let’s now take a look at the extremely original way with which Foucault affirms, beyond all ontology, that the statements concern the fact that “there is language”. It is advisable to not understand this affirmation as an absolute: to define the statement as a function of existence which refers to a domain of coexistence provided with a materiality, without being comprised of fragments of matter and rather using the material conditions to establish a link, means dispensing with any absolute use of “there is” and “there is language”. It’s about “reveal[ing] the fact that, here and there, in relation to possible domains of objects and subjects, in relation to other possible formulations and re-uses, there is language.”[1]. This “there is” or also that “function of existence”, uniquely concerns the fact that the components of a statement are given together in accordance with a rule, and the discrimination of that reality does not presuppose that language severs a preceding muteness. That’s why it rather consists of an operation. From that point of view, The

Archeology of Knowledge is thrown into contrast with Raymond Roussel of 1953: in this first book, the way Roussel works relies on several technical metaphors: in order to grasp the “procedures” of Roussel, Foucault talks about the architecture of scenes and the construction of language2, about a “technique of secret verticality”[2], about the “machinery of language”[3]. But those were just metaphors in the sense that literature remained an autonomous domain, without its homogenity being conceptualized with non-linguistic operations. At the same time, Roussel’s procedure remains linked to ontology, albeit a fantastical one: “now the language experiences the distance of repetition only as a place for the mute apparatus of a fantastical ontology.”[4] This ontology, fantastical or not, ultimately related this art of writing in all its pecularities to an experience of destruction and death: “Chance is not a play of positive elements, it’s an infinite opening, renewed at the very moment of annihilation.”[5] Process is what Foucault calls the manner in which Roussel, after he had developed narratives, while randomly exploring assonances and the ambiguities without rhyme or reason within language, came back to his point of departure, exposing the fragility of meaning. He saw in that fragility a literary experience of destruction and of the approach of death in life. The destruction of the appearance of meaning that Roussel excels in is said to be an experience of death within life. Writing transposes a fundamental experience of language:

“Roussel’s whole work up to the Nouvelles Impressions revolves around a singular experience (I mean that it must be stated in the singular), the link between literature and this nonexistent space, which, underneath the surface of things, separates the internal from the visible face, and the external from the invisible core. There, between what is hidden within the evident and luminous in the inaccessible, the task of language is found.”[6] By rendering this moment as absolute, Deleuze has understood Foucault as an ontology of the visible and the expressible. But this reading is still connected too closely to a simple opposition of things and discourse, which Foucault rightly undermines.

The latter explicitly distanced himself from his point of departure. When The Archeology of Knowledge thinks about practices of language as operations, that is no longer a metaphor, that is to say a transposition in the work with words of an experience of life and death that is supposed to be fundamental and “cast” in the relation of meaning and non-meaning. The ability to discern statements is not possible other than through suspending that ontological calling of literature just as one suspends grammatical analyses, logical propositions and language as a system structured by signifiers. Describing without metaphor what is operational in the practice of signs, demands this distance taken with respect to ontology, be the latter philosophical (Heidegger, Badiou) or literary (Roussel, Blanchot).

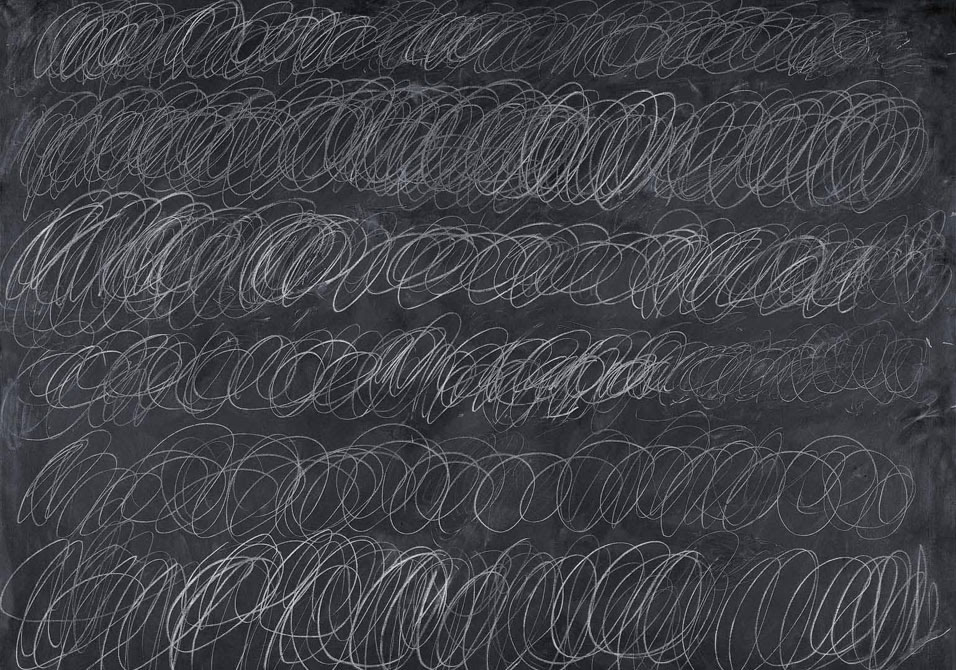

In this respect, a painting can be a statement, just as a sequence of letters and numbers can. That is very much the topic of the short text “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (1973). Foucault certainly takes up here the subject of his study on Roussel which, between the words and the visible scenes that these words constructed, made “a small clear and transparent bond” perceptible, which indicates that the words never coincide with the things they evoke. But the issue is now completely different: the paintings of Magritte not only make the space perceptible that separates the drawing of the pipe put on the easel – itself precariously located on a school floor – from its negative annotation: “this is not”. The issue is not only to underline the noncoinciding of the visible and sayable which the negation indicates in what is said. The issue is rather to consider the painting as the result of an operation – of which the canvas bears the trace: Foucault puts forth the hypothesis that, if there are two pipes in the last version of the painting, it is because the inscription results from the unravelling of a calligramm, that is to say from doing something. In order for this act to become reality, it is advisable to compare various works that are gathered under the name “This is not a pipe” and to take note of the fact that, if, on the last canvas of that name, a big pipe floats above the canvas on which in turn a smaller pipe and the phrase “this is not a pipe” appear, these constant cross references result from the transpositions the painter executes from one version of the painting to another. Between words and things, operations transform the principle on which the painting rests: the resemblance is not equivalent to the affirmation of a representative bond anymore. The resemblance is not equivalent to a similitude that language could say anymore. Klee and Kandinsky take up a different operation: Klee put writing and image on the same level of reality thereby putting the subordination of one of the orders under the other to an end, usually the image under the written sign. When it comes to Kandinsky, he realized “a double effacement simultaneously of resemblance and of the representative bond” (CP 34). The lines that are more and more present in these paintings are things, not more and not less than the object bridge, church or rider. There is no model anymore. When these three painters carry out movements that fall under three distinct “processes” it shows well that there is not one fundamental operation which would provide the connection of language to being while in truth revealing their essential inadequacy. If there are effects of reality between the visible and signs, it because one is always within operations, which could or could not be detectable, like statements. One “knows very well”, normally, that painting requires a technique. But what Foucault adds functions differently: it renders an operation graspable in the procedure of the painter that is of the same register as statements. That is why his “there is” is not an ontological or ontic[7] proposition and “this is not” is not equivalent to the “there is” of Lacan in “there is no sexual relationship”. The real is not “extimate” to logic. The materiality of the conditions that contribute to forming a statement, as well as the operative character of the relation between the heterogenic components of the statement, are very different from the direct if negative articulation of the sexual non-relationship in the writing of the logical functions in Lacan.

One could fruitfully pursue the comparison with Lacan who himself redefined what he called discourse in the Seventies. But such is not my intention today. I would simply like to show that the individualization of statements has required the practice of a break in thinking that is unmatched. Since the institutional materiality of the statement is a type of reality that is very difficult to discern or, as Foucault has said in a seemingly simple way, to describe. It is by accomplishing to describe language in a transversal fashion with respect to its logical organization, its signifying structure, and its syntactical and rhetorical components that he succeeds in determining positivities: “Neither hidden, nor visible, the enunciative level is at the limit of language…” (A.K., p.124)

[1] A.K., p. 125 2 RR, p. 34.

[2] Op.cit., p. 36.

[3] Op.cit., p. 38.

[4] Ibd.

[5] Op.cit., 46.

[6] Op.cit., 122.

[7] “This is not a pipe” is thus not defined by the Heideggerian opposition of ontic and ontological that Lacan remarks on in Seminar XI: “It came at a particularly good point, in that when speaking of this gap one is dealing with an ontological function, by which I thought I had to introduce, it being the most essential, the function of the unconscious.” Op.cit., p. 29. But Lacan hesitates since, a few pages later, he abandons the duality ontological/ontic and prefers to give the unconscious the status of the ethical: “If I am formulating here that the status of the unconscious is ethical, and not ontic, it is precisely because Freud himself does not stress it when he gives the unconscious its status.”, Op.cit., p. 34. In Encore, Lacan comes back to this break which he seeks with respect to the distinction between the ontic and the ontological. He isn’t satisfied solely with the ethical status of the unconscious. He underlines rather that “Being – if people want me to use this term at all costs […] is the being of signifierness.” Op.cit., p.71. And this semblance of being, produced by signifierness [signifiance], has to be connected to the relation between the unconscious as a system of letters and the sexual non-relationship: “The unconscious is structured like the assemblages in question in set theory, which are like letters. Since what is at stake for us is to take language as (comme) that which functions in order to make up for the absence of the sole part of the real that cannot manage to be formed from being (se former de l’être) – namely, the sexual relationship – what basis can we find in merely reading letters?” Op.cit., p. 48.